Smart Citizens in the Data Metropolis

Last November Mara attended the Smart City expo and wrote this article. It was originally published in the website of the Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona.

With the Smart City Expo having taken place in Barcelona last week, it is a good opportunity to pose some questions about how these ‘smart cities’ are prefigured, and about the ways in which cultural institutions and citizenship will be affected as a result of their deployment. New opportunities, new challenges.

Suddenly, one of the classic media artworks has become an apt metaphor. In Jeffery Shaw’s 1989 Legible City, users hop on a stationary bicycle and navigate their way through the streets of a city of words, a 3D simulation made up out of meanings. A city of data. Twenty-three years later, the essence of smart cities is not too distant from Shaw’s scenarios.

To start with, contemporary cities are going through a change that may seem obvious but is fundamental: it will no longer be necessary to go and look for information in one of the temples of the past, or to absorb it through the media. Data flows through closed and open networks, on earth and in the skies. Data from sensor networks or M2M (Machine to machine) connections, information provided by users of social networks, and crowdsourcing will come down from the cloud and enhance physical urban space. The great challenge of how to turn all that data into meaningful, useful information still remains, but the data and the devices that ‘sense’ it and put it into circulation already exist and are connected.

Increasingly, companies that design user experiences are starting to develop physical interfaces or mobile apps that integrate data with city life. Urbanscale, by Adam Greenfield is a good example, with its UrbanFlow service that augments the city’s screens (at bus and train stations, streets, etc.) with “designed and situated” information that allows citizens to find what they are looking for, plan routes, and even participate in civic life.

For more examples we don´t need to look further than Barcelona, where the company WorldSensing has set up sensors to capture traffic data that can then help drivers to find a parking space using a mobile app. Along similar lines, the Barcelona-led European project iCity seeks to open up urban infrastructures that interested agents can enhance with data in order to offer services of public interest that improve urban life. A parking metre that offers information on the air quality at its location, an app that lets you know whether the public swimming pool or part are packed to overflowing, a ticket vending machine for public transport that offers you the chance to participate in a popular consultation as well as selling you your weekly ticket.

Apocalyptic and integrated, utopia and dystopia. As usual, our ideas about the future are influenced by strongly conflicting ideas. There are those who believe that smart cities imply the rise of an Orwellian society, where technology will be exclusively in the hands of monopolies and authoritarian governments, and will only be used to monitor and control citizens. Security and privacy are still a problematic frontier. On the other hand, more optimistic perspectives believe that technology and data will open up doors to transparency, civic participation and the emancipation of sections of society that were previously excluded. They also defend the sustainable city, in which the community itself, by means of its access to open data, reduces its energy use or adopts more responsible behaviour. The Tidy Street project in Brighton is a great example of a citizen initiative to self-regulate electricity consumption.

This is why the smart city meme must go far beyond resource optimisation and hi-tech efficiency projects. While technology corporations offer city councils smart city- in-a-box type solutions that require large technological investments even though there is no conclusive proof that a system that works in one city will work in a different one, research suggests that smart cities will not exist unless citizens are at the centre of the equation.

This year, the Institute for the Future and the Rockefeller Foundation released “A Planet of Civic Laboratories“, a report that suggests that in order for cities to be truly smart, data must generate inclusion and development. Top-down solutions proposed by big technology companies are not enough. According to the report, in today’s cities there is a growing and opposing force of entrepreneurs, hackers, and “citizen hacktivists” who are pursuing a different vision of the future city. Their pitch is that urban data in the form of information can promote cities that are more democratic, more inclusive and more resilient.

These do-it-yourself (DIY) urbanists use open-source technologies and cooperative structures for citizen-driven initiatives, strengthening social commitment and ensuring that technological process remains in line with civic interests. Along these lines, projects such as Smart Citizen (a kit containing sensors for measuring environmental indicators and connecting via the online platform Cosm), by Barcelona FabLab, and DCDCity, incubated at MediaLab Prado, nourish the smart city concept from the other side: open code, do-it-yourself philosophy and citizen participation. Given this situation, what is the role of schools and cultural centres? How can these projects be integrated into the cultural agenda and the educational curriculum? How will ‘smart citizens’ be educated?

In the future, successful cities will almost certainly have to integrate these two models. Ideal solutions combine large-scale platforms with big citizen-led innovations. This integration is already taking place to a certain extent, but public administrations need to shape and encourage it as part of an agenda of openness, transparency and inclusion.

Cities are like living organisms with a spirit that extends way beyond the technological network and infrastructure. Human communities make and sustain a city’s specific DNA, and it is these particularities – sometimes whimsical or even inexplicable – that must be taken into account when designing innovation in a city context.

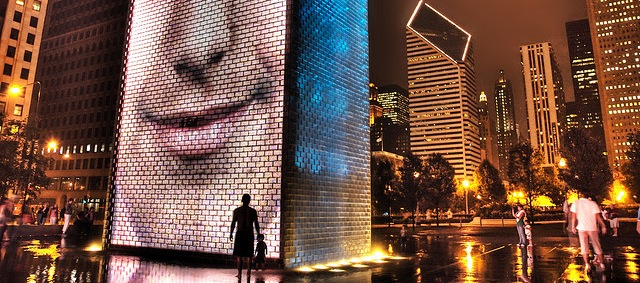

It is also worth imagining what new infrastructures will reconfigure the landscape of hyperconnected postmodern cities, digesting the information that flows through them in real time, from traffic control to Facebook ‘likes’, air pollution levels, breakdowns on train networks, and road problems reported through services like FixMyStreet.

What shape will the new, hyperconnected flaneur take, now that our right to get lost in the city or discover unexpected spots while looking for a late-night pharmacy is no longer taken for granted? Perhaps one possible role of cultural institutions will be to imagine new urban experiences that enrich physical space with a certain poetry, to return some serendipity to the street experience, or to help us resignify data or reencounter furtive space. To finish with, a curious anecdote that illustrates the contrasts of this zeitgeist: on the way to the airport, the taxi driver ironically said to me: “New taxi drivers don’t know their way around the city any more. They go wherever the GPS tells them. Do you know what I call this thing? A Guide-For-Stupid.”

photo credit: Stuck in Customs via photopin cc