Netmob, a small conference dedicated to the study of mobility and network datasets (primarily sourced from mobile phones, although a couple of Foursquare based studies managed to sneak in), took place at the beginning of May at the MIT Media Lab. These kind of massive behavioural datasets paint a picture of human dynamics at an unprecedented level of detail, at city scale and beyond, and have proven invaluable for research in social sciences, statistical physics (of human behaviour), urban planning and computer science alike. Despite the fact that no official proceedings are published, other than a book of abstracts (pdf 40MB) and the D4D book (pdf 122MB), the quality of work was high, perhaps due to the big names on the organising committee.

The first day was a special session for the Orange D4D challenge in which around 150 teams of researchers tackled a wide range of development related problems using the anonymised and aggregated digital traces of 5 million Orange mobile customers in Cote d’Ivoire. It was great to see that Orange seem genuinely excited to be taking a lead in the ‘data philanthropy’ agenda, although they were also clearly concerned that research based on large scale personal data be conducted in a responsible manner, lest data sharing and extracting its value become politically and commercially impossible. For example, they urged researchers to be careful not to attract ‘big brother’ accusations, however misguided they may be, and to be sure to understand the local context before reaching potentially sensitive conclusions (e.g., do community detection algorithms reveal tribal divisions or merely economic regions?). UN Global Pulse also had a large presence at the conference, and were extolling the huge potential of large scale data analysis to help tackle global development issues – exciting times for the data scientist. Below I summarise some personal highlights of the work presented at D4D and Netmob.

Data 4 Development

In “AllAboard: a system for exploring urban mobility and optimizing public transport using cellphone data” Berlingo et al. (prize winners) develop a number of techniques for inferring public transport trips from people’s movement between cell towers (passive crowdsourcing), which is then fed into a system which optimises the transit network. This kind of system could potentially be applied to any city in the world, even more easily in cities that already capture trips with automated fare collection systems, such as London. However, an important consideration is that public transport routes are often planned in order to encourage trips in order to bolster activity in certain regions. Indeed, the network structure and cost of public transport will largely determine the OD matrix, so optimising based solely on existing flow patterns may not be enough.

In “Crowdsourcing Physical Package Delivery Using the Existing Routine Mobility of a Local Population”, McInerney et al. propose a novel method of package delivery which exploits people’s regular travel patterns. Taking inspiration from work on mobile ad-hoc networks, mobility data is analysed to determine the best path between participants to get a package to its destination, with minimal disruption to the participants route.

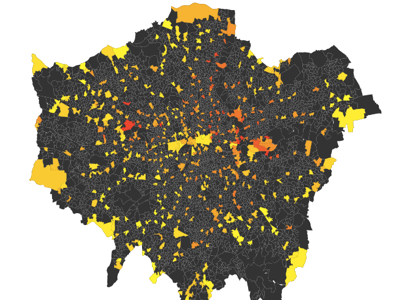

Mao et al. present a number of interesting findings including discovering a number of features of call activity that correlate with socioeconomic indicators around economic centres. Particularly interesting are correlations with the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality. They also find that a community detection algorithm delineates customers along boundaries between wealthier and poorer areas. In my own submission with Afra Mashadi and Licia Capra (which was mentioned as a ‘significant project’) we took a similar approach to mining the call data, and found a number of features which correlated strongly with poverty levels in different parts of the country. We then demonstrated how this might be used to produce poverty maps at a finer level of granularity.

First prize winners Lima et al. made full use of both communication and mobility patterns in “Exploiting Cellular Data for Disease Containment and Information Campaigns Strategies in Country-Wide Epidemics”. By comparing simulations of information diffusion over the communication network and infection spread over a physical contact network, they showed that information campaigns may be a more effective means of disease containment and prevention than physical quarantine efforts.

Mobility Modelling

The next two days of Netmob contained a lot of other interesting work using different data sets. Yang and Gonzales presented an extension to the radiation model of human mobility which includes a parameter to account for different scales. They showed that it performs better than the original radiation model and the doubly constrained gravity model, which has many more parameters to fit. Deville et al. showed that a simple scaling relationship exists between the exponents of mobility patterns and spatial-social networks, meaning that we could estimate the flow of traffic between areas from the flow of communication. An example of GPS mobility traces was given by Horanont et al., this time looking at visitor numbers in Japan. A nice 3D visualisation shows the numbers of visitors per building in the Odaibo area of Tokyo, something that certainly couldn’t be measured from CDR alone. Most haunting however, was an animation depicting the effect on mobility of the 2011 earthquake. The familiar flashes of movement across the city abruptly halted as the quake struck. Then individuals could be seen making long and slow walks home before the public transport network finally came back online late at night.

Crowdsensing

Salnikov and Lambiotte presented a brilliant example of incentivised crowdsensing in “Late For Good”. Smart phone users are offered a convenient service which automatically fills and submits delay claim forms to the Belgian rail operator in return for passively submitting regular GPS coordinates. Thus, what users lose in battery life, they gain in compensation and satisfaction. So far they have received around 600k data points, far from the billions often found in call detail records (CDR) datasets but with substantially increased spatial and temporal resolution.

Well-being

Back to Cote d’Ivoire but using data from a mobile operator other than Orange (and therefore not part of the D4D challenge), Gutierrez et al. present what might be known as the ‘top-up’ model of wealth. The reasonable, but as yet unvalidated, hypothesis is that top-up behaviour reflects the wealth of the phone user (i.e., frequent small top-ups = poor, infrequent large top-ups = rich). Using the model to produce a proxy wealth indicator they map the average and diversity of wealth of different regions in the country. The final (and to my knowledge, original) example of using CDR to map wealth/poverty at the conference came from Frias-Martinez et al. who presented “CenCell”. This is a system that takes as input, for a sample of census areas, ground truth socioeconimic level indicators and numerous mobility, social, and usage features of CDR data, and applies some advance machine learning techniques to build a classification model which can produce estimates for the remaining census areas. Posed as a binary classification problem (i.e., predict high or low socioeconomic level) and tested on data from a Latin American country the system was able to achieve up to 76% accuracy. Blumenstock and Toomet present an interesting study of ethnic segregation in cities, in the specific case of Estonia, which has a long history of in- and out-migration of Russians. Using language as a reliable proxy for ethnicity they are able to look in detail at social homophily and physical segregation, and more importantly the effect of migration and urbanisation on community integration.

Connected by Location

Toole et al. looked at the similarity between people’s movement patterns and how this similarity relates to social relations. Among their findings are that tie strength correlates with movement similarity and that individuals tend to share their most important locations with their top four social contacts. This means that movement similarity could be used as a proxy for a social network. Along similar lines, but this time using Foursquare data, Brown et al. develop a place-based model of social network formulation in cities, inspired by Feld’s theory of focused organisation which says that friendships often form around common foci. Their model reproduces many structural characteristics of real social networks. It is nice to see that a model based on location preference has similar results to those using mechanisms such as preferential attachment. It would be interesting to see if this approach was better at reproducing spatial characteristics of social networks such as aggregated tie strength between neighbourhoods within cities. This may also be significant for urban planners who want to think about the effects of the physical structure on promoting healthy social relationships.

Temporal Dynamics

Finally, Miritello et al. looked at medium-term temporal dynamics of communication patterns and produced several important results (see this blog post with visualisations and link to full paper). Notably, they found a high rate of decay among social ties – only 60% of a month’s social ties are present in the next month – meaning that a long period of observation (at least 6 months they suggest) is needed to gain an accurate picture of social relationships. Likewise, this means that a long period will be required to gain an accurate picture of flows between different parts of the city. They also found that individuals have a limited and fixed capacity for communication (although it differs between people), and reveal a distinction between ‘social keepers’, who maintain a fixed set of contacts, ‘social explorers’, who replace old contacts with new over time, and ‘social balanced’, whos rate of link birth/death is proportional to their capacity. Unexpectedly, simulations show that social keepers receive information in the network first, and given the connection between information diffusion and economic advantage, these new temporal properties of social networks may prove useful in modelling the well-being of neighbourhoods.